The UK has a low pay problem that is getting worse. The number of people on low pay is up a quarter of a million year on year to more than five million, or around a fifth of workers. The proportion of workers in low paid jobs has been the same for nearly two decades despite the success of the National Minimum Wage in eradicating extreme low pay. For many on low pay, stagnant wages plus inflation makes it hard to afford the basics: housing, bills and the weekly shop. So improving pay is essential to increasing household incomes and tackling child poverty. Employers and the government need to do a lot more to support those stuck in low pay and looking for a way out.

The recent increase is not a statistical blip. The Work Foundation has highlighted the long-term trend of “hollowing out” of the labour market, with middle-skilled jobs disappearing as roles at the bottom and top of the labour market expand. IPPR concluded that over the next decade more low paid jobs will be created than middle or high-paying ones. More jobs are clearly good news, with employment rates now close to record highs. But unless pay at the bottom increases the problem of working poverty will keep growing and the cost to the state of topping-up pay that is not enough to live on will keep increasing.

The challenge isn’t only that a fifth of workers are low-paid. It’s also that many are stuck in low pay for the long term. The Commission recently published research that reveals who gets stuck in low pay, who escapes and why.

Over the course of a decade, only a quarter of low-paid workers escape low pay altogether, with two thirds ‘cycling’ in and out of low pay and one in ten stuck in low pay for every single one of the ten years. Those who get stuck are more likely to be single parents, have disabilities or live in the North East or the West Midlands. These findings are a reminder of the enduring nature of low pay and lack of routes out.

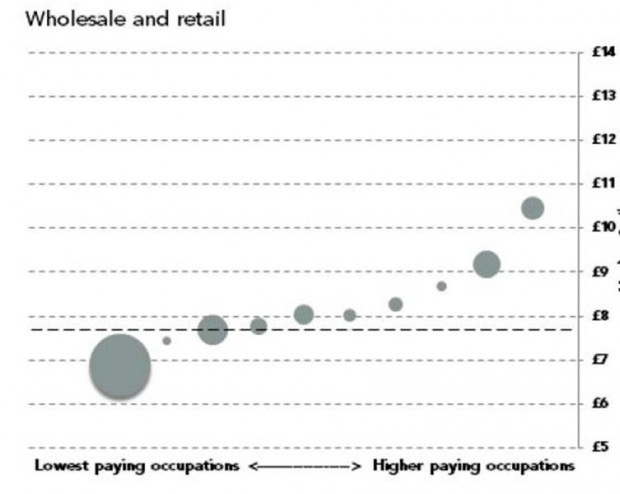

An interesting finding was that many low-paid workers interviewed for the study believed that the downsides of promotion – such as increases in responsibility, changes to working arrangements, changes to relationships with colleagues and additional hours – outweighed the benefit of pay increases. One reason for this is likely to be the relatively small increases in pay available from moving into assistant and junior managerial roles, illustrated in the chart below. Another is the fact that many in low-paid work – especially if they have children – lose at least three quarters of any increase in pay through taxes and reductions in in-work benefits and tax credits. This poses real challenges for government in tackling working poverty.

Tackling low pay requires a concerted effort from actors across society. Government does not have all the levers at its disposal; employers are key to unlocking access to better jobs and pay. The Commission recommends a number of straightforward actions that can be taken to make a difference:

- Employers – first, employers need to do more. Paying the Living Wage where possible and, where not, taking action to increase productivity to move towards paying it in the future. Being more active in advertising internal promotion opportunities and updating HR processes so discussions about progression are part and parcel of normal management. Changing job design to increase productivity and help reduce staff turnover. Earlier this week, the UK Commission for Employment and Skills (UKCES), in partnership with the CBI and the TUC, published a report highlighting several things employers can do to help people progress in work.

- Government – second, the Commission called for the Government to coordinate a society-wide strategy to make the UK a Living Wage country by 2025 and expand the role of the Low Pay Commission as part of this. If progress is to be made on tackling low pay it is essential that the government provide leadership, not least through paying staff it employs directly, or indirectly through its contractors, the Living Wage. While the Commission agrees that the National Minimum Wage should continue to be set at a rate that does not damage employment prospects, it does not believe that passively sitting back and hoping that pay at the bottom will increase in the future will lead to progress. The box below highlights key things that a strategy on low-pay and progression to drive faster progress should cover.

- Local authorities – finally, a major block to some people taking more hours or responsibility is access to good quality and flexible childcare. The offer for low-income households is there – now local authorities must ensure those who are eligible take up the provision and that it is of high standards.

Addressing low pay can reduce poverty and increase mobility. It has the potential to stop today’s generation of poor children becoming tomorrow’s generation of poor parents. Employers, government and others need to grasp this challenge as no one actor can solve this alone. The Commission believes that if economic recovery is not matched by a social one there is a risk of Britain becoming ever more divided; we can and must do better to rise to the challenge.

1 comment

Comment by Gordon Morris posted on

This is clearly a problem caused by low pay, low grade jobs, with few prospects of meaningful progression, and ... low paying employers. The many stories about well-qualified (if, on occasions, inappropriately qualified) graduates – and postgraduates – strongly suggests that we are wasting talent (in people) and investment (in education). As a nation we cannot rely on “retail”-type jobs to drive economic growth. We must invest in industries with the potential (“green”?) to employ those we educate, and for those we educate to use their skills and knowledge for the benefit of the wider economy. This will take government investment and policies designed to drive up wages. At the moment we have neither- imagination and ambition and less of the laissez faire ideologically-driven “hope this will work” approaches that seem to be producing stagnation and increased inequality and poverty.